In the world of aromatic and spiced plants, few have reached the global relevance that ginger enjoys. This root, known for its pungent flavour and intense aroma, has travelled the globe since the ancient trade routes of Asia. Today, it is an essential ingredient in kitchens, rituals, and traditional preparations.

Its versatility has earned it a prominent place in gastronomy and natural formulations. For professionals working with herbs and medicinal plants, ginger is an invaluable resource—not only because of its unique sensory profile, but also due to the wealth of cultural and technical knowledge surrounding it.

In this article, we delve into the history, characteristics, cultivation methods, and traditional uses of this age-old rhizome. A comprehensive overview offering inspiration, knowledge, and context for professionals wishing to work with this root of immense potential.

What is Ginger?

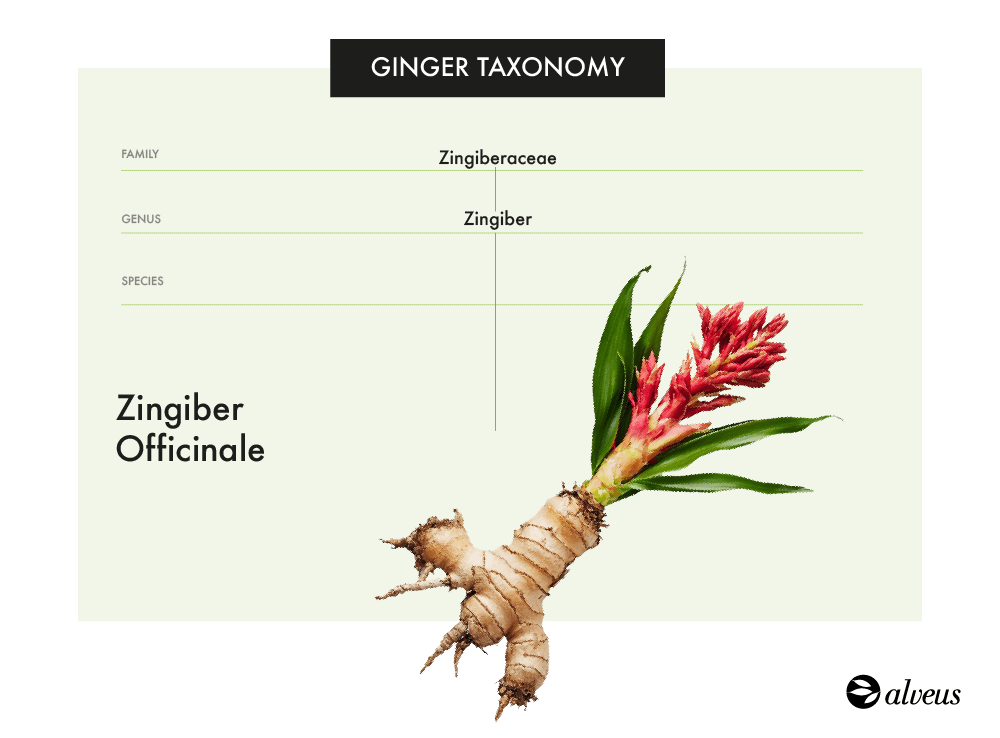

Ginger is a rhizome (an underground stem) from the plant Zingiber officinale, native to Southeast Asia. Despite its rough, knotted appearance, its interior is juicy, with a strong, slightly spicy flavour.

Its use goes far beyond direct consumption—it features in culinary blends, traditional preparations, and processed products such as powders, essential oils, preserves, and more.

The word “ginger” derives from the Sanskrit śṛṅgavera, meaning “horn-shaped”, about the rhizome’s distinctive form. Over time, it evolved into zingiberis in Greek, then zingiber in Latin, which forms the basis of the current botanical name.

Although commonly used to refer to the rhizome, “ginger” also applies to the whole plant, Zingiber officinale, a perennial herb of the Zingiberaceae family.

Origin and Historical Spread

Ginger has its roots in Southeast Asia, where it is believed to have been cultivated for over 3,000 years. Regions such as India and southern China are among its most recognised points of origin, owing to their ideal climates and long-standing traditions in its cultivation and use.

From its early use in rituals, cuisine, and healing practices, ginger became a key player in the great ancient trade routes, thanks to its value as an aromatic spice and its durability in dried form. It became a sought-after commodity in global markets.

For centuries, it travelled along major trade routes:

- The Spice Route, connecting Southeast Asia to the Middle East and Europe via the Indian Ocean.

- The Silk Road facilitated its spread overland from China to the Mediterranean across Central Asia.

Ginger reached Europe in Roman times but rose to peak prominence in the West during the Middle Ages. Considered a luxury spice, its price rivalled that of pepper or saffron.

In parallel, ginger gained importance in various cultural traditions:

- In Indian Ayurvedic medicine, it became part of digestive formulas, tonics and decoctions.

- In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), it was used to balance Qi (energy flow) and in warming infusions. Learn more about TCM and other Asian herbal traditions in this post.

- In Asian cuisines, it has long been a key ingredient in sauces, broths, and marinades.

- In medieval European gastronomy, it featured in both savoury and sweet dishes, as well as spiced beverages.

Thanks to its adaptability and widespread appeal, ginger has become a commercial spice, a symbolically and culturally rich ingredient around the world.

Botanical Characteristics of Ginger

Zingiber officinale is a perennial medicinal plant of the Zingiberaceae family, which also includes turmeric (Curcuma longa) and cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum).

The ginger plant can grow between 90 cm and 1.5 metres tall, with upright, simple stems. Its leaves are long and lance-shaped, reaching 20–25 cm, arranged in two rows along the stem. The flowers, grouped in dense spikes, are yellow with purplish or reddish accents.

The rhizome, its most valued part, grows horizontally underground. It has a fibrous texture, a pale yellow to golden interior, and a pungent, aromatic flavour due to its volatile compounds.

Harvesting takes place once the plant completes its vegetative cycle, selecting mature but not aged rhizomes to preserve optimal sensory qualities.

Current Ginger Production

Today, ginger is grown in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide, with India, China, Nigeria, Indonesia, and Thailand as leading producers.

India leads in both volume and diversity of cultivars, with a significant share destined for domestic consumption and a portion for export.

Soil and climate conditions, farming techniques, and post-harvest processes also influence its sensory profile.

Types of Ginger in the Market

Several types and commercial forms of ginger are available, not always reflecting distinct botanical varieties, but rather factors such as rhizome age, processing, and growing region:

- Common ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe): the most widely available form, sold fresh, dried, or ground.

- Baby ginger: young, tender rhizome without fibres. Milder in flavour and used fresh, in pickles or gourmet dishes.

- White ginger: not a separate variety, but mature ginger with the skin removed. Lighter in colour and milder, often used in infusions and delicate blends.

- Thai ginger: prized for its lower fibre content and balanced flavour. Common in Southeast Asian cuisine.

- Jamaican ginger: recognised for its complex aroma and mild heat, widely used in baking and drinks.

- Chinese ginger: moderately flavoured, one of the most commercially widespread.

- Nigerian ginger: highly aromatic and spicy, mainly used in powdered or extract forms.

These variations make ginger a highly adaptable ingredient, suitable for a wide range of professional applications.

Chemical Composition of Ginger

Ginger stands out for its complex chemical profile, responsible for its characteristic flavour and its broad traditional use.

Its most representative compound is the [6]-gingerol, an active principle from the phenolic compound family, known for contributing its typical pungency (a spicy and warming sensation) in its fresh state.

The gingerol, main compound in fresh ginger, changes with heat. When dried or cooked at high temperatures, it transforms into shogaols, which are even more pungent. In contrast, when gently simmered or boiled, it produces zingerone, with a milder and sweeter taste.

This chemical transformation is key to understanding the various culinary and traditional applications, depending on how it is prepared: fresh, dried, or powdered.

In addition to these, ginger contains a variety of volatile essential oils, such as zingiberene (with a woody aroma), citral (citrusy note), and borneol (fresh scent), all of which contribute to its warm, spicy, and subtly citrus aroma. These substances may also vary according to the type of ginger, its origin, and processing method.

These qualities have been the subject of numerous scientific studies aiming to further explore their potential, always within the framework of their age-old tradition.

Forms of Ginger

Ginger is available in several forms, each with unique characteristics that affect flavour, aroma, texture, and shelf life—key factors for its use in gastronomy and other sectors.

Fresh Ginger

The most common form for culinary and infusion use. It has a vibrant, spicy flavour and a firm, juicy texture. Refrigeration is required to preserve freshness and flavour.

Dried Ginger

Produced by drying the fresh rhizome. It has a more concentrated flavour and spicier punch due to the transformation of gingerol into shogaols. Widely used in spice blends and seasoning.

At our B2B shop, we offer dried ginger pieces and jelly-style ginger chunks—a practical format popular in many markets.

Ground Ginger

Finely ground dried ginger. It offers a milder aroma and flavour than fresh ginger but is extremely versatile, used in baking, spice mixes, and processed foods. It stores well in airtight containers.

Pickled and Crystallised Ginger

Used as a garnish or sweet ingredient in baking. These forms offer a unique balance of sweetness and heat.

Essential Oil and Extracts

Liquid concentrates of ginger are used in aromatherapy, cosmetics, food or pharmaceutical formulations. Due to their high concentration, careful handling is essential.

For professionals, choosing and storing the appropriate ginger form is key. Fresh ginger requires refrigeration and rapid use, while dried and powdered forms have longer shelf lives when kept away from moisture and direct light.

Traditional and Contemporary Uses of Ginger

Ginger in Cuisine

Ginger is a staple ingredient in many global cuisines, used fresh, dried, or powdered to add flavour and texture to curries, marinades, soups, sauces, desserts, and baked goods.

In Japan, pickled ginger (gari) is traditionally served with sushi, while in India, it’s a key ingredient in masala chai, the spiced tea blend.

In Europe and the Americas, ginger features in classics such as gingerbread and ginger biscuits, especially around Christmas. It also stars in drinks like ginger ale and ginger beer, loved for their distinctive flavour in cocktails and modern cuisine.

Ginger Infusions and Beverages

Ginger infusions are a popular and versatile way to enjoy the root, appreciated for their intense, slightly spicy flavour and refreshing aroma. Historically, they’ve been valued not just for taste but for their reputed benefits, contributing to ginger’s medicinal plant status.

Ginger tea can be made from fresh, dried, or powdered ginger, often combined with lemon, honey, cinnamon, or aromatic herbs, forming part of cultural and popular traditions across the globe.

These infusions are enjoyed hot or cold, and are now common in specialist tea shops and homes alike.

Beyond flavour, infusions offer a simple way to enjoy ginger’s sensory qualities as part of a daily routine or a varied menu offering.

Cosmetics, Perfumery, and Aromatherapy

Ginger is also used in the production of essential oils, creams, and lotions. Its warm, spicy, and slightly sharp aroma makes it a popular ingredient in perfumery and aromatherapy.

However, it should be used with care, as pure extracts can irritate the skin.

Ethnobotanical and Traditional Herbal Use

Ginger holds a prominent place in traditional medical systems such as Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), where it has been used for centuries.

In Ayurveda, it is regarded as a “warming” plant, believed to stimulate the digestive fire (agni) and support internal balance. In TCM, it is appreciated for its capacity to “disperse cold” and help mobilise energy, forming part of numerous preparations aimed at restoring harmony in the body.

These traditions have integrated ginger in a variety of forms, from simple decoctions to complex formulas combined with other herbs. According to these systems, the choice between fresh and dried ginger depends on the intended effect, as each form is traditionally believed to offer different properties.

Beyond these frameworks, ginger has long been valued in many cultures as a digestive ally and a general wellness tonic, a recognition that continues today through its use in both herbal practices and modern natural formulations.

Final Thoughts on Ginger

With its millennia-old history and unique chemical profile, ginger remains a staple ingredient across multiple domains—from cuisine to traditional medicine and cosmetics.

Its versatility and rich sensory appeal make it a valuable resource for professionals working with plants, offering endless possibilities in both culinary and therapeutic contexts.

Understanding its forms, properties, and cultural contexts allows us to make the most of its potential, keeping alive the ancestral knowledge that has made ginger an indispensable root in cultures around the world.

Bringing this wisdom into professional practice paves the way for both innovation and respect for tradition.