With centuries of history, Pu Erh tea is one of the great treasures of Chinese tea culture. Originating in Yunnan Province, this fermented tea is known for its sensory complexity and its capacity to evolve, both in flavour and in cultural and economic value.

Its controlled ageing process, which can span years or even decades, makes it a living product that continues to develop after production.

This blog post offers a comprehensive guide to Pu Erh, exploring everything from its history to the most renowned growing regions and its traditional commercial forms.

We also cover sensory analysis from a professional standpoint, Gong Fu Cha preparation techniques, and key considerations for storage. A must-read for sommeliers and industry professionals looking to deepen their understanding of one of the world’s most complex teas.

What Is Pu Erh and Why Does It Stand Out Among All Teas

Pu Erh tea is a type of post-fermented tea originating exclusively from Yunnan Province, in southwest China. Unlike other teas, Pu Erh undergoes a controlled microbial fermentation process that profoundly alters its chemical and sensory profile.

This unique process allows Pu Erh to evolve, developing complex layers of flavour and aroma, making it comparable to products like wine or aged cheese.

Botanically, Pu Erh is made from the tea plant Camellia sinensis var. assamica, a large-leaf variety native to Yunnan. Many of the plants used are centuries or even millennia old (known as gushu), which adds to their biocultural value.

It is not so much the plant variety that defines Pu Erh, but rather the post-fermentation process the leaves undergo after harvest. To learn more about Pu Erh tea production and the types of Pu Erh based on fermentation, check out this other post on our blog.

Thanks to its organoleptic complexity, ageing potential and deep cultural roots, Pu Erh tea has gained increasing interest in gastronomy, tea collecting, and professional tasting circles. It is now seen as one of the most sophisticated tea categories on the global stage.

Origin and History of Fermented Pu Erh Tea

The name Pu Erh comes from the city of Pu’er in Yunnan Province, China, which served for centuries as a major hub for tea collection and trade. Tea leaves harvested in the surrounding mountains were pressed into cakes or bricks to ease transport and storage.

Throughout these long journeys, humidity, pressure and time caused spontaneous biochemical changes in the tea, resulting in a sensory and chemical profile completely distinct from other teas.

By the 20th century, especially from the 1970s onwards, Chinese authorities and tea cooperatives developed a controlled method known as Wo Dui, which replicates natural ageing through accelerated microbial fermentation.

This innovation gave rise to ripe (shou) Pu Erh, making it more accessible and standardised for global markets.

Pu Erh Growing Regions

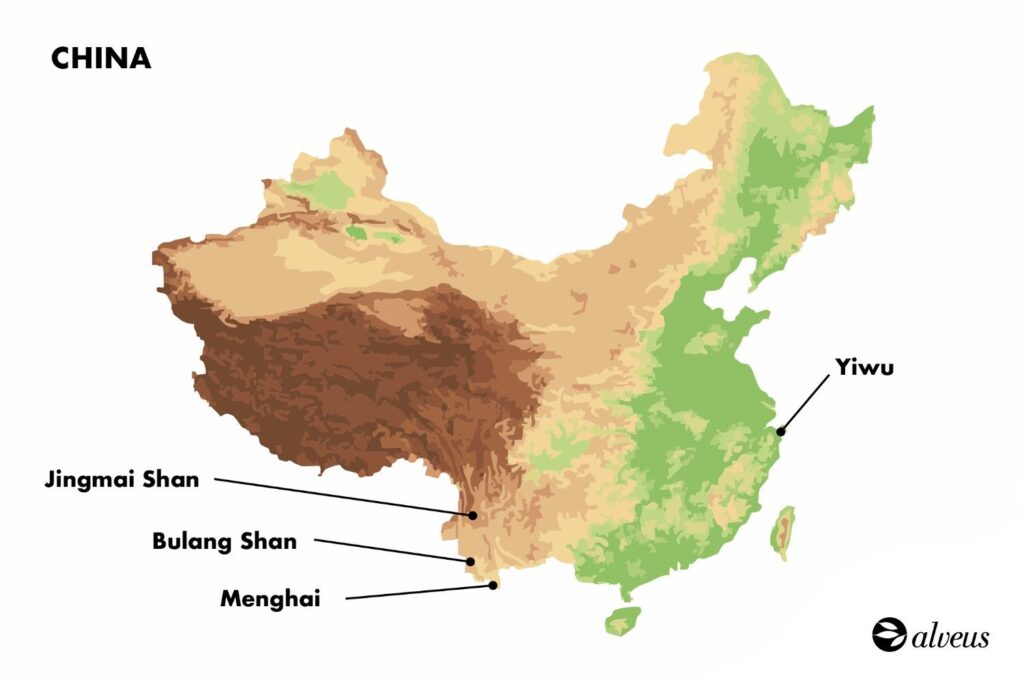

Yunnan Province, in southwest China, is the only region with a Protected Designation of Origin for Pu Erh tea.

This extremely diverse area — with altitudes from 500 to over 2,000 metres — features micro-terroirs where geography and ecology shape unique sensory profiles. Climate, soil type, altitude, and forest ecology vary between sub-regions, creating distinctive teas.

Menghai

One of the most emblematic and stable production areas, home to historic tea factories.

Its warm and humid tropical climate favours a consistent, controlled fermentation — ideal for producing ripe (shou) Pu Erh. Teas from Menghai are dense, earthy, naturally sweet, and have a silky texture.

Bulang Shan

Located near the Burmese border, Bulang Mountain is known for its high altitude, iron-rich red soils, and a high concentration of ancient tea trees (gushu).

The resulting teas are powerful, with a bold initial astringency balanced by noble bitterness and a lasting sweet aftertaste (hui gan).

Yiwu

Renowned for its artisanal tea heritage, Yiwu blends well-preserved forests with traditional processing.

Its teas offer a more delicate profile with floral aromas and silky texture. Low tannin impact makes them especially appealing to those seeking a more approachable young Pu Erh that ages gracefully.

Jingmai Shan

Jingmai stands out for its biodiversity and the presence of ethnic minority cultures (such as the Bulang and Dai), who have developed sustainable cultivation systems. Teas from Jingmai are well-balanced, with mild acidity and great sensory clarity.

Classification and Types of Pu Erh

Pu Erh tea can be classified according to two main criteria, though there are other distinctions: fermentation type and commercial form.

Both factors influence the tea’s organoleptic properties, market value, storage needs, and ageing potential.

By Fermentation Type

Although we explore this in more depth in our post on dark teas, it’s helpful to recall the two main Pu Erh categories by fermentation:

- Sheng (raw) Pu Erh: Produced without artificial fermentation. It matures naturally over the years, gradually developing vegetal, fruity, mineral and eventually earthy notes.

- Shou (ripe) Pu Erh: Undergoes accelerated fermentation using controlled humidification techniques (known as wo dui). The result is an earthier, more accessible flavour profile from the first brew, without the need for extended ageing.

By Commercial Form

Beyond fermentation, Pu Erh is primarily sold as pressed tea, although loose-leaf forms also exist.

Tuocha (nest)

Pressed tea in a bowl-like shape. Its compactness and small size make it practical for export and single servings.

* Pu Erh Mini Tuo Cha Mini Tuo Cha Pu Erh available for wholesale purchase from our Alveus B2B platform.

Bingcha (cake)

Pressed into a round disc, typically 357 grams — now a market standard. This shape supports both trade and even ageing.

Jincha

Similar to tuocha but even denser. Its high compression slows down ageing, favouring prolonged and stable development.

Maocha

Loose, unpressed leaves. The raw material for all pressed formats, typically used for professional tastings, quality control and harvest evaluation.

Zhuancha (brick)

Rectangular, compact Pu Erh, historically used for caravan trade. Its stackable shape remains popular in traditionally high-consumption regions like Tibet.

* Pu Erh Brick BIO is available for wholesale purchase from our Alveus B2B online shop.

Organoleptic Profile and Sensory Categories

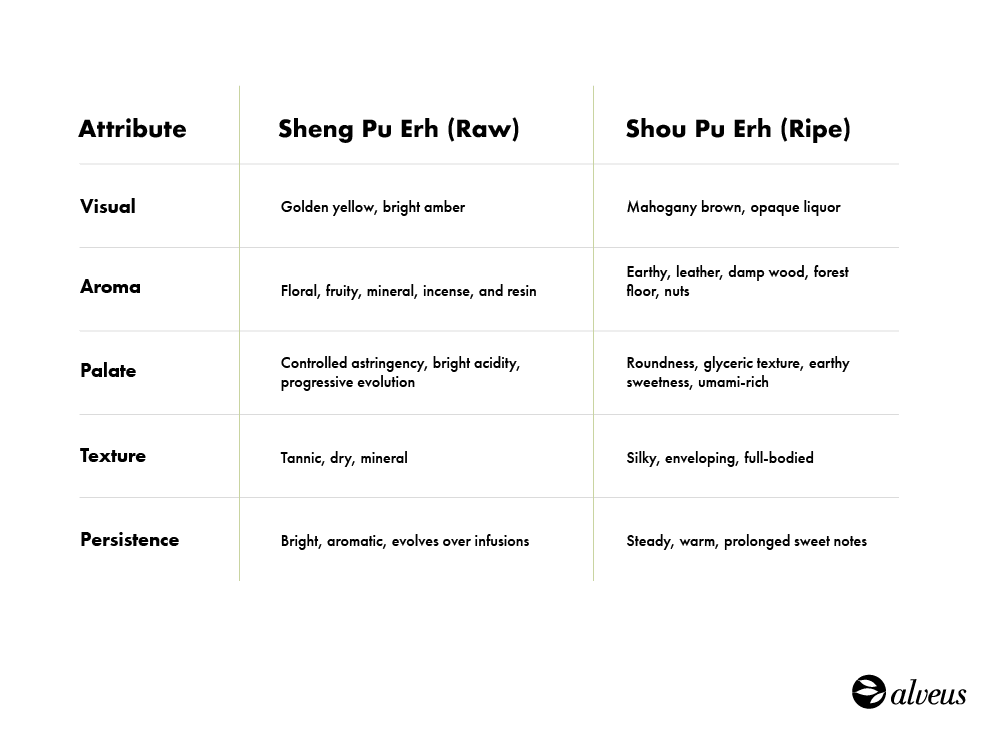

Pu Erh tea is characterised by a complex sensory profile, distinct from the classical spectrum of green, white, or oxidised teas.

Its sensory richness stems from the botanical and geographic origin of the leaves, as well as the post-fermentation and ageing processes, which produce a wide array of evolving nuances.

Key Sensory Attributes

In professional analysis, key sensory dimensions and attributes include visual appearance, aromatic definition, mouthfeel, texture, and retronasal persistence.

There are also intermediate profiles influenced by terroir, ageing time, and pressing method.

Chemical and Microbiological Composition of Pu Erh Tea

Pu Erh tea is known for its complex chemical composition, derived from the tea plant and the post-fermentation process it undergoes.

Throughout this process, enzymatic, microbial and environmental factors interact, transforming the tea’s structure and generating unique compounds with organoleptic and functional implications.

Key Bioactive Compounds

- Polyphenols and catechins: Modulate bitterness and contribute to antioxidant activity.

- Gallic acid: Linked to digestive and detoxifying properties, with a rounder form of astringency.

- Theaflavins and thearubigins: Contribute to colour, body, and some astringent notes.

- Free amino acids: Such as theanine, which brings umami, mouthfeel smoothness, and modulates bitterness perception.

- Caffeine: Varies in concentration depending on Pu Erh type and leaf material.

Microbiology of Pu Erh

During natural (Sheng) or induced (Shou) fermentation, various microorganisms interact with the tea leaves. Among the most studied are:

- Aspergillus niger

- Penicillium spp.

- Rhizopus spp.

- Various environmental yeasts

These microorganisms partially break down lignin and tannins, softening the texture and altering the tea’s aromatic profile.

Storing and Preparing Pu Erh Tea

Brewing Parameters

Pu Erh can be brewed using Western-style methods or the traditional Chinese Gong Fu Cha method, ideal for appreciating its more complex nuances.

Western-Style Preparation (Cup or Teapot)

- Dosage: 3–5 g per 250 ml of water

- Temperature: 95–100 °C

- Infusion Time: 3–5 minutes

- Reinfusions: Up to 3 times without losing body

Gong Fu Cha Technique (Recommended for Tasting and Sales)

- Dosage: 5–8 g per 100 ml

- Temperature: 100 °C

- Infusions: 8 to 12 rounds, increasing steeping time progressively (from 5 to 10 seconds)

- Utensils: Gaiwan or Yixing clay teapot

The Gong Fu Cha method allows for advanced technical evaluation of Pu Erh, revealing its progression, infusion after infusion. This technique brings out the tea’s structure, balance, and potential for transformation — key elements in sommelier-level tasting and quality assessment.

Storing Pu Erh Tea

Unlike other teas, Pu Erh should not be stored in airtight containers. Its ageing process requires oxygen and stable environmental conditions.

Optimal Storage Conditions:

- Relative Humidity: 60–70%

- Temperature: 20–25 °C

- Environment: Dry, no direct light or strong odours (as tea absorbs them)

- Ventilation: Continuous, without aggressive air currents

- Materials: Porous containers like bamboo boxes, clay, rice paper or untreated wood

Final Thoughts on Pu Erh

Pu Erh tea represents one of the most complex and valued categories in the tea world, not only for its unique processing, but also for its ability to transform over time. Analysing it requires the understanding of botanical and geographical factors as well as microbial, chemical and sensory variables.

For tea professionals, Pu Erh offers a rich field of technical study. Preparing it through methods like Gong Fu Cha enables a structured evaluation of its evolution — a crucial element in assessing quality and ageing potential.

Understanding its various styles, origins, pressing forms and storage parameters is essential for proper valuation, informed selection and offering an optimal experience to the consumer. This specialist knowledge is vital for professional purchasing, as well as in contexts such as fine dining, tasting, or tea collecting.